The Asset Pipeline and Import Maps

A web site consist of many more files than just the HTML documents we have been generating up to now: css files, image files, font files, javascript files, ...

The asset pipeline is rails' way of preparing theses files for publication using the current state of knowledge regarding web performance.

By referring to this guide, you will be able to:

- keep your assets in the right place

- have all your assets compiled and minified for production

Slides - use arrow keys to navigate, esc to return to page view, f for fullscreen

1 Using external CSS and JavaScript

You can always include CSS and JavaScript code form other sites.

/* File app/views/layouts/application.html.erb */

<title>Demo</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://cdn.simplecss.org/simple.min.css">

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/chart.js"></script>

There are several big CDN sites that offer many different JavaScript libraries:

And there are some specialized sites:

2 Web Performance

What do we mean by 'web performance'? From the viewpoint of one user, the crucial value is the time it takes from requesting a page (by clicking a link or button, or typing in an URL) to having the page displayed and interactive in your browser. We will call this the 'response time'.

From the publishers point of view it might also encompass the question of how many users you can serve (with acceptable response time) on a given server. If you look at the question of how to serve more users in case of more demand you enter the realm of 'scalability'. This is a more advanced question that goes beyond the scope of this guide.

2.1 Myths About Performance

If you have never studied this subject you might still have

an intuition about where performance problems come from.

Many beginners are fascinated by details of their programming

language like: will using more variables make my program slower?

or is string concatenation faster than string interpolation?.

These 'micro optimizations' are hardly ever necssary with modern programming languages and computers. Using Rails, Postgres and a modern hosting service you will have no trouble serving hundreds of users a day and achieving adequate performance for all of them.

Trying to 'optimize' you code if there is no problem, or if you don't know where the problem is, will make your code worse, not better.

Donald Knuth stated this quite forcefully:

"The real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimization is the root of all evil" -- Donald Knuth

Only after you have measured the performance factors that are relevant to your project, and only after you have found out which part of the system is causing theses factors to go over the threshold of acceptable values, only then can you truly start to 'optimize'.

2.2 Measuring Web Performance

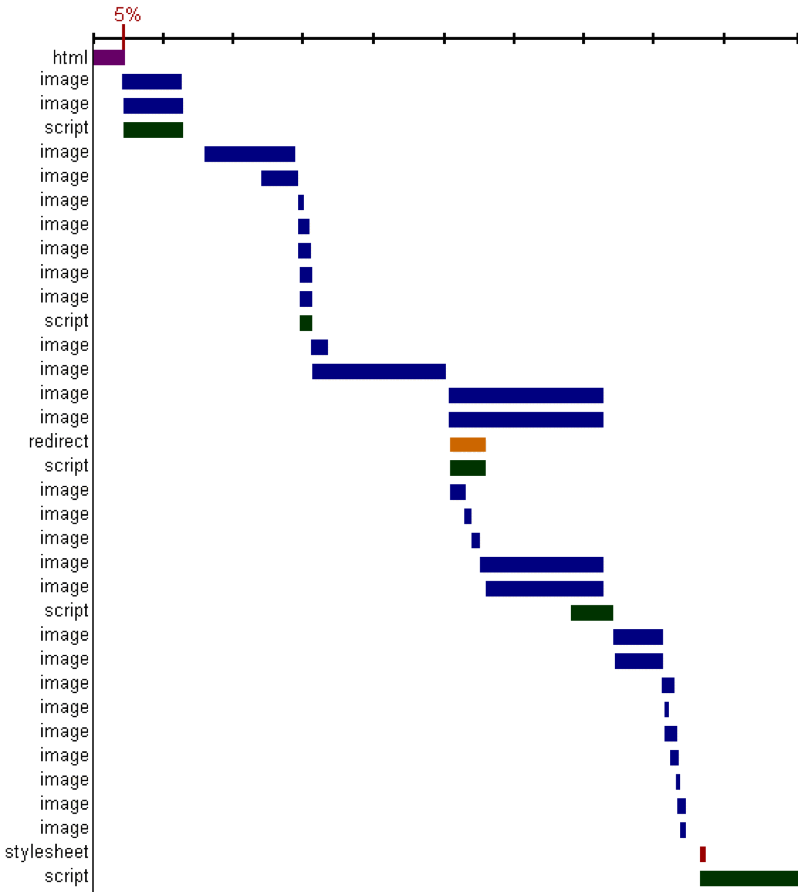

The "exceptional performance group" at Yahoo published the browser addon

yslow in 2007. It measures performance and displays the timing

of the different HTTP connections as a "waterfall graph":

(Image from Steve Souders talk at Web 2.0 Expo in April 2008)

Each bar is one resource being retrieved via HTTP, the x-axis is a common timeline for all. The most striking result you can read from this graph: the backend is only responsible for 5% of the time in this example! 95% of time is spent loading and parsing javascript and css files and loading and displaying images!

This graph was later integrated into the built in developer tools of several browsers, and into the online tool webpagetest

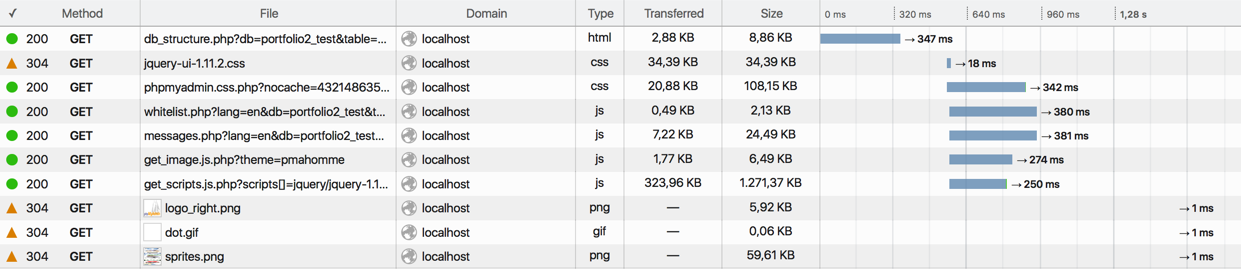

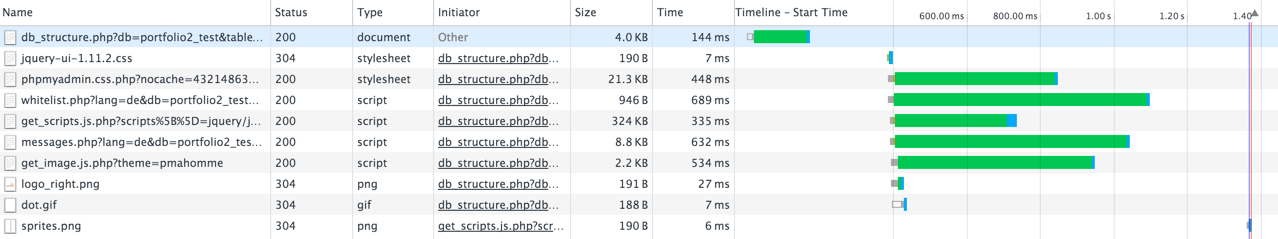

Firefox

Chrome

2.3 Rules...

Yahoo first published 14 rules for web performance in 2007, based on the measurements back then:

- Make Less HTTP Requests

- Use a Content Delivery Network

- Avoid empty src or href

- Add an Expires or a Cache-Control Header

- Gzip Components

- Put StyleSheets at the Top

- Put Scripts at the Bottom

- Avoid CSS Expressions...

- Make JavaScript and CSS External

- Reduce DNS Lookups

- Minify JavaScript and CSS

- Avoid Redirects

- Remove Duplicate Scripts

Even with changing browsers and protocols some of these are still very valid today, while others have become less important or are not valid at all.

As a web developer you should always keep an eye on the changing landscape of web performance!

2.4 Less HTTP Requests?

Making less HTTP Requests was a main goal in performance optimization for many years. Many JavaScript files were "bundled" - combined into one, the same for CSS. Icon Fonts were used to combine many small image files into one file.

On the other hand the HTTP protocol itself was improved again and again, to make repeated requests to the same server "cheaper":

- HTTP/2 server HTTP requests can be multiplexed over a single TCP connection

- HTTP/3 uses UDP instead of TCP

In 2025 HTTP/3 is supported by all common browsers except safari and use by more than a third of the top 10 million websites.

So today this "first rule" for avoiding HTTP requests can be relaxed.

3 How Rails helps with Performance

The Rails asset pipeline was introduced in Rails 3.1 in the year 2011. The original asset pipeline is called "sprockets", since Rails 8 new projects start with "propshaft". Both and can do the following:

- Optimize images

- Create several versions of pixel images

- transpile to CSS (e.g. SASS, LESS)

- Minify and combine several CSS files into one

- Create CSS Sprites

- transpile to JavaScript (e.g. typescript, babel, coffeescript)

- Minify and combine several JavaScript files into one

JavaScript can also be handled in other ways, we will focus on using the asset pipeline for images and css.

There are two main folders:

- you put source files in

app/assets/* - you configure which files in which sub-folder are built in

app/assets/config/manifest.js - if you use bundling, you define which files to include in the css bundle in

app/assets/stylesheets/application.css - if you use the asset pipeline for javascript, you define which files to include in the js bundle in

app/assets/javascript/application.js - files for publishing are created in

public/assets/*

The public folder contains static files only. It will be served by the web server directly, without going through the Rails stack.

The expires header for the files in public/assets/ should be set to a far future date.

3.1 Rails Environments

The Asset Pipeline works differently in different Rails Environments. There are three environments that exist by default:

development- this is the environment you have been working in until now,

- it is optimized for debugging, shows error messages and the error console.

testing- this is used for running the automatic tests.

production- this is how the finished app will run after it is published,

- it is optimized for speed and stability.

How each environment behaves is configured in files in config/environments/*.rb.

The development environment is used by default on your machine. If you deploy your app to a webserver, production will be used there.

3.2 development Environment and the Asset Pipeline

In development the asset pipeline will not write files to public/assets. Instead

these files will be created on the fly, and not be conactenated. The two lines

in your Layout:

# app/views/layouts/application.html.erb

<%= stylesheet_link_tag "application", media: "all", "data-turbolinks-track" => true %>

<%= javascript_include_tag "application", "data-turbolinks-track" => true %>

Will each result in a number of links. Here an example from a real project:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/asset-files/search-a01b0css?body=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/asset-files/slider-974d5css?body=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/asset-files/static-7fe63css?body=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/asset-files/token-input-f5febcss?body=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/asset-files/wizzard-9a065css?body=1" />

<script src="/asset-files/jquery-4075ejs?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/jquery_ujs-f9f4ajs?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/portfolio/portfolio-78775js?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/swfobject-40913js?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/jquery-uploadify-702eajs?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/application-d7727js?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/can-custom-c11b4js?body=1"></script>

<script src="/asset-files/easySlider-6386djs?body=1"></script>

3.3 production Environment and the Asset Pipeline

When you deploy to production, you deployment process will run rake assets:precompile,

which generates the files in public/assets, including public/assets/manifest-md5hash.json.

If you look at the generated HTML code on the production server,

you will only find two links (plus some code to handle IE 8): in production

the many css files have been concatenated into one application*.css, and

all JavaScript files have been concatenated into one application*.js:

<link href="/assets/application-dee0187.css" media="screen" rel="stylesheet" />

<!--[if lte IE 8]>

<link href="/assets/application-ie-d369224.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<![endif]-->

<script src="/assets/application-c51a73.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

3.4 Fingerprinting for better Expiry

The filenames mentioned in the last chapter all contain a part that seems random:

- you named the file

slider.css - but it shows up as

slider-974d585dcb6f5aec673164664a4e49d5.css

Where do the extra characters come from and what do they mean?

These extra characters are the "fingerprint". It is computed as a hash from the full content of the file. If only one byte changes in the file, the fingerprint will be different.

Let's look at the effect that fingerprinting has on caching:

- I create a file

slider.css - the asset pipeline publishes it as

slider-abc.css(simplified) and an expiry date in the year 2099 - rails displays the webpage with a

link rel=stylesheettag that points atslider-abc.css - a browser loads the page for the first time, loads

slider-abc.cssand keeps this version of the file forever

If the same user comes back to my webpage a year later, the browser will load

the new html page. this will still contain a link rel=stylesheet tag that points at slider-abc.css.

slider-abc.css is still in the browser cache, this will be used. No need to load it.

Another year later I change something in slider.css and deploy the web application again. Now what happens:

- I edit the file

slider.css - the asset pipeline publishes it as

slider-xyz.css(simplified) and an expiry date in the year 2101 - rails displays the webpage with a link rel=stylesheet tag that points at

slider-xyz.css

Now if a user comes back to my website, their browser will see a new URL for the style sheet.

The cached style slider-abc.css is ignored, the new file slider-xyz.css will be loaded

and added to the cache.

This way we automatically handle one the the two hard problems in computer science: cache invalidation.

3.5 Using assets in your views

To include the concatenated and fingerprinted css file, use this in your layout:

<%= stylesheet_link_tag "application" %>

To use an image example.svg stored in app/assets/images/example.svg use

<%= image_tag 'example.svg ' %>

3.6 Using fonts

To use fonts in the asset pipeline first create a fonts directory

in app/assets. This is where you can store your *.woff2 files.

In app/config/manifest.js you need to add

//= link_tree ../fonts

Now you can use these font files in your stylesheets. But beware: the font files will get new filenames because of the fingerprints.

So instead of writing

/* file fonts.css */

@font-face {

font-family: "stardos_stencil";

src:

"../fonts/stardosstencil-bold-webfont.woff2"

format("woff2"),

"../fonts/stardosstencil-bold-webfont.woff"

format("woff");

font-weight: 700;

font-style: bold;

font-display: swap;

}

You need to use the method font_path. This also implies naming

the stylesheet .css.erb so that ruby can be used:

/* file fonts.css.erb */

@font-face {

font-family: "stardos_stencil";

src:

url("<%= font_path('stardosstencil-bold-webfont.woff2') %>"

format("woff2"),

url("<%= font_path('stardosstencil-bold-webfont.woff') %>"

format("woff");

font-weight: 700;

font-style: bold;

font-display: swap;

}

4 User Generated Content

The asset pipeline handles assets that are added by developers during development. Images uploaded by users in production are handled by activestorage.

5 JavaScript

JavaScript can be added to an application in several different ways.

5.1 Using JavaScript with import maps

Make sure you have the gem importmap-rails in your Gemfile or add it with bundle add importmap-rails.

If you already have a file bin/importmap you are all set up. If not, you need to run this once:

rails importmap:install

From now on you can add npm packages for the frontend with importmap pin. For example:

$ bin/importmap pin unicode-emoji-picker

Pinning "unicode-emoji-picker" to vendor/javascript/unicode-emoji-picker.js via download from https://ga.jspm.io/npm:unicode-emoji-picker@1.3.9/index.js

Pinning "scrollable-component" to vendor/javascript/scrollable-component.js via download from https://ga.jspm.io/npm:scrollable-component@1.2.1/index.js

Pinning "unicode-emoji" to vendor/javascript/unicode-emoji.js via download from https://ga.jspm.io/npm:unicode-emoji@2.5.0/index.js

Here I requested one module, but it came with two dependencies. All three modules

were downloaded do my machine and added to the folder vendor/javascript.

See the file config/importmap.rb for the complete list of pinned imports.

The files from /vendor/javascript are handled like other assets: they

will get a new filename with a fingerprint and in production

they will be copied to public/assets/.

In app/views/layouts/application.html.erb you use

<%= javascript_importmap_tags %>

If you look at the generated html code of your app you will find several new JavaScript features at work:

<script type="importmap" data-turbo-track="reload">{

"imports": {

"application": "/assets/application-d8a8613a.js",

"unicode-emoji-picker": "/assets/unicode-emoji-picker-c8299061.js",

"scrollable-component": "/assets/scrollable-component-a8230eb7.js",

"unicode-emoji": "/assets/unicode-emoji-d50af150.js"

}

}</script>

<link rel="modulepreload" href="/assets/application-d8a8613a.js">

<link rel="modulepreload" href="/assets/unicode-emoji-picker-c8299061.js">

<link rel="modulepreload" href="/assets/scrollable-component-a8230eb7.js">

<link rel="modulepreload" href="/assets/unicode-emoji-d50af150.js">

<script type="module">import "application"</script>

A script tag with type importmap can define "bare" names for importing JavaScript modules. So instead of writing

import "https://myapp.at/assets/unicode-emoji-picker-c8299061.js";

we can now use the bare module name:

import "unicode-emoji-picker";

The link tags with rel modulpreload tell the browser to load these files

as soon as possible, so they will be available when an import-statment is encountered.

5.2 Writing your own JavaScript modules

The entrypoint for you own JavaScript is app/javascript/application.js.

From there you import and call you own modules:

import Emoji from "src/emoji";

// all the code that needs to run after DOMContentLoaded:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

Emoji(document);

})

Here a module src/emoji.js is imported. This file also needs

to be "pinned". You can do this for all the files in app/javascript/src at once with

pin_all_from 'app/javascript/src', under: 'src'

In emoji.js you can import the module "unicode-emoji-picker" by referencing it by it's bare name:

import "unicode-emoji-picker";

function Emoji(scope) {

const picker = scope.querySelector('unicode-emoji-picker');

picker.addEventListener('emoji-pick', (event) => {

let emoji = event.detail.emoji;

console.log(emoji);

});

}

}

export default Emoji;

5.3 Importmaps and Caching

When the app is deployed, the javascript file will be published with fingerprints:

/assets/application-d8a8613a.js

/assets/unicode-emoji-picker-c8299061.js

/assets/scrollable-component-a8230eb7.js

/assets/unicode-emoji-d50af150.js

But when you look inside the files, they reference other modules by their bare names.

Dependencies need to be updated regularly to stay ahead of security problems.

You can do this with importmap:

$ bin/importmap outdated

| Package | Current | Latest |

|----------------------|---------|--------|

| unicode-emoji-picker | 1.3.9 | 1.4.0 |

1 outdated package found

$ bin/importmap update

Pinning "unicode-emoji-picker" to vendor/javascript/unicode-emoji-picker.js via download from https://ga.jspm.io/npm:unicode-emoji-picker@1.4.0/index.js

With this update the file vendor/javascript/unicode-emoji-picker.js has changed. This

will result in a new fingerprint. Browsers that already have the other javascript

file in cache will only need to load on new file.

(Contrast this to classic "JavaScript bundling" where all files are concatenated into one giant bundle, and every change leads to reloading the whole bundle.)

6 Further Reading

- Rails Guides: The Asset Pipeline (with propshaft)

- Souders(2007): High Performance Web Sites. O'Reilly. ISBN-13: 978-0596529307.

- Souders(2009): Even Faster Web Sites. O'Reilly. ISBN-13: 978-0596522308.

- The Web Performance (Advent) Calendar new every year