1 Model Basics

Rails Models are classes that represent tables in the database.

Rails implements the Active Record pattern in a class called ActiveRecord.

All the models in a Rails project inherit from ActiveRecord.

# file app/models/Tweet.rb

# this is the Tweet model that you create

class Tweet < ApplicationRecord

end

# file app/models/application_record.rb

# this file already exists

class ApplicationRecord < ActiveRecord::Base

primary_abstract_class

end

1.1 The Mapping

A quick overview of how Objects and Database relate when using ActiveRecord in Rails:

Database Ruby on Rails

--------------------------- --------------------------

table courses class Course

in the Database in file app/models/course.rb

one row in the table one object of the class Course

an attibute in the table a property of the object

SELECT * FROM courses WHERE id=7 Course.find(7)

2 The Model

Look at the model generated in file app/models/tweet.rb. Later you will add validations, associations to other models and the business logic here.

2.1 The model in the console

You can use the Rails console to work with

the model interactively. This is similar to the ruby console irb

but with your Rails app already loaded.

Any changes you make are really written

to the development database!

rails console

if you just want to play around and not make changes to the database use

rails console --sandbox

instead.

2.2 Finding a model

The database table always has a primary key id. You can use this

key to find a specific record:

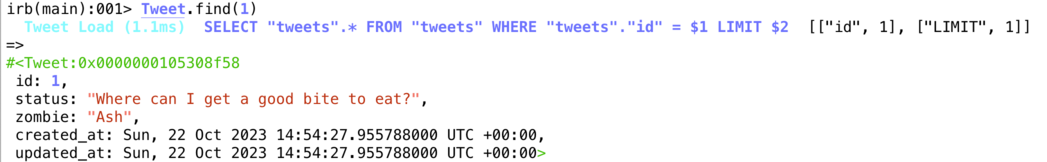

When you type in Tweet.find(1) into the Rails console, you get two answers:

First (in color) it shows you the SQL query sent to the database. In this case

SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE "tweets"."id" = ? LIMIT ?. You can see

that prepared statements are used, and that a limit is always placed on the number

of answers.

After the Arrow (=>) the Rails console shows the return value of the command

you typed in. Here this is an object. The console prints out the details of this

object using the inspect method.

From now on we will use this slightly shortended format to show Rails console input and output:

railsconsole> Tweet.find(1)

=>

#<Tweet:0x0000000105308f58

id: 1,

status: "Where can I get a good bite to eat?",

zombie: "Ash",

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.955788000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.955788000 UTC +00:00>

(We will leave out the SQL, and some timestamps.)

2.3 Accessing the properties

You can access the properties of the model object as if it were a hash or through method names:

railsconsole> t = Tweet.find(3)

=> #<Tweet id: 3, status: "I just ate some delicious brains.", zombie: "Jim">

railsconsole> t.status

=> "I just ate some delicious brains."

railsconsole> t[:status]

=> "I just ate some delicious brains."

railsconsole> t.zombie

=> "Jim"

railsconsole> t[:zombie]

=> "Jim"

2.4 CRUD = Create, Read, Update, Delete

Let's see how ActiveRecord implements the four important capabilities of persistance:

2.5 Create

t = Tweet.new

t.status = "I <3 brains."

t.save

With new you create a new object just in memory. It is not stored in the

database yet and does not have an id yet. You can set its properties.

The save method tries to save it to the database.

On the Rails console you can see how the properties are nil in the beginning.

After saving to the database some of the properties are set:

railsconsole> t = Tweet.new

=> #<Tweet:0x0000000106688358 id: nil, status: nil, zombie: nil, created_at: nil, updated_at: nil>

railsconsole> t.status = "I <3 brains."

=> "I <3 brains."

railsconsole> t.save

TRANSACTION (3.8ms) BEGIN

Tweet Create (9.2ms) INSERT INTO "tweets" ("status", "zombie", "created_at", "updated_at") VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4) RETURNING "id" [["status", "I <3 brains."], ["zombie", nil], ["created_at", "2023-10-22 17:12:31.990939"], ["updated_at", "2023-10-22 17:12:31.990939"]]

TRANSACTION (2.0ms) COMMIT

=> true

railsconsole> t

=>

#<Tweet:0x0000000106688358

id: 4,

status: "I <3 brains.",

zombie: nil,

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 17:12:31.990939000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 17:12:31.990939000 UTC +00:00>

2.6 Read

There are many ways to read data from the database. We already saw find which

uses the primary key and always returns one object. The method where is used for more general select - where SQL statements.

t1 = Tweet.find(3)

t2 = Tweet.where("created_at > '2023-10-21'")

t3 = Tweet.where(zombie: 'Ash')

In the Rails console you can see the return values: where returns serveral objects in the end.

railsconsole> t2 = Tweet.where("created_at > '2023-10-21'")

Tweet Load (1.0ms) SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE (created_at > '2023-10-21')

=>

[#<Tweet:0x00000001066070a0

...

railsconsole> t2

=>

[#<Tweet:0x00000001066070a0

id: 1,

status: "Where can I get a good bite to eat?",

zombie: "Ash",

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.955788000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.955788000 UTC +00:00>,

#<Tweet:0x0000000106606f60

id: 2,

status: "I <3 brains.",

zombie: "QueenRotten",

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.957318000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.957318000 UTC +00:00>,

#<Tweet:0x0000000106606e20

id: 3,

status: "I just ate some delicious brains.",

zombie: "Jim",

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.958430000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.958430000 UTC +00:00>,

#<Tweet:0x0000000106606ce0

id: 4,

status: "I <3 brains.",

zombie: nil,

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 17:12:31.990939000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 17:12:31.990939000 UTC +00:00>]

2.7 Update

With update - as with new before - we see the difference between the

object in memory (t) which can be changed and the object in the database

which is only changed when t is saved back to the database.

t = Tweet.find(3)

t.zombie = "EyeballChomper"

t.save

In the Rails console you can see that the UPDATE statement in SQL really

only changes the one changed attribute.

Plus the property updated_at is automatically set.

railsconsole> t = Tweet.find(3)

Tweet Load (10.0ms) SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE "tweets"."id" = $1 LIMIT $2 [["id", 3], ["LIMIT", 1]]

=>

#<Tweet:0x0000000106603ae0

...

railsconsole> t.zombie = "EyeballChomper"

=> "EyeballChomper"

railsconsole> t.save

TRANSACTION (4.6ms) BEGIN

Tweet Update (18.0ms) UPDATE "tweets" SET "zombie" = $1, "updated_at" = $2 WHERE "tweets"."id" = $3 [["zombie", "EyeballChomper"], ["updated_at", "2023-10-22 17:17:34.242526"], ["id", 3]]

TRANSACTION (0.9ms) COMMIT

=> true

2.8 Delete

To delete both the object in memory and in the database use destroy.

t = Tweet.find(3)

t.destroy

On the console you can see how destroy is translated to DELETE in SQL.

destroy gives the last version of the model as a return value.

railsconsole> t = Tweet.find(3)

Tweet Load (12.4ms) SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE "tweets"."id" = $1 LIMIT $2 [["id", 3], ["LIMIT", 1]]

=>

#<Tweet:0x0000000106600b60

...

railsconsole> t.destroy

TRANSACTION (2.3ms) BEGIN

Tweet Destroy (3.5ms) DELETE FROM "tweets" WHERE "tweets"."id" = $1 [["id", 3]]

TRANSACTION (1.1ms) COMMIT

=>

#<Tweet:0x0000000106600b60

id: 3,

status: "I just ate some delicious brains.",

zombie: "EyeballChomper",

created_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 14:54:27.958430000 UTC +00:00,

updated_at: Sun, 22 Oct 2023 17:17:34.242526000 UTC +00:00>

2.9 Chaining ActiveRecord methods

Let's look at the example of using where again: the return value was of class ActiveRecord::Relation:

railsconsole> t3 = Tweet.where(zombie: 'Ash')

Tweet Load (9.6ms) SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE "tweets"."zombie" = $1 [["zombie", "Ash"]]

=>

[#<Tweet:0x00000001062858c8

...

railsconsole> t3.class

=> Tweet::ActiveRecord_Relation

This class also supports all the ActiveRecord methods. This means

we can chain several wheres together. ActiveRecord can combine them

into a complete SQL statement:

railsconsole> tweets = Tweet.where("created_at > '2023-10-21'").where(zombie: 'Ash')

Tweet Load (1.0ms) SELECT "tweets".* FROM "tweets" WHERE (created_at > '2023-10-21') AND "tweets"."zombie" = $1 [["zombie", "Ash"]]

In fact there are many more methods we might want to use for chaining:

Tweet.limit(3)

Tweet.order(:zombie)

Tweet.select(:created_at, :zombie, :status)

Tweet.where("created_at > '2023-10-21'").

where(zombie: 'Ash').

order(:zombie).limit(3)

For the last three lines: Normally the dot is placed in front of the method when chaining. Here it is placed at the end, to enable copy-and-paste to the Rails console)

You can use the method to_sql to see the SQL Statement produced by the chained methods:

railsconsole> Tweet.select(:created_at, :zombie, :status).

where("created_at > '2020-10-01'").

where(zombie: 'Ash').

order(:zombie).

limit(3).to_sql

=> SELECT "created_at", "zombie", "status"

FROM "tweets"

WHERE (created_at > '2020-10-01')

AND "zombie" = 'Ash'

ORDER BY "zombie" ASC

LIMIT 3

The order of the methods is not relevant. You can also save an intermediate step to a variable, and then chain more methods to that variable later on:

railsconsole> query = Tweet.where("created_at > '2020-10-01'").

order(:zombie).limit(3)

railsconsole> query.select(:created_at, :zombie, :status).

where(zombie: 'Ash').to_sql

=> SELECT "created_at", "zombie", "status"

FROM "tweets"

WHERE (created_at > '2020-10-01')

AND "zombie" = 'Ash'

ORDER BY "zombie" ASC

LIMIT 3

2.10 Further reading

- The Rails Guides give a good introduction to a subject area:

- Rails Guide: Active Record Basics

- Rails Guide: Active Record Query Interface

- Use the Rails API documentation to look up the details: